Executive Summary: Private markets are being pitched as the next frontier for everyday investors—with Vanguard now joining the push. But don’t believe the hype. Alternative investment funds are expensive, opaque and illiquid. Their risk-reducing qualities are oversold. And unless you have access to the best managers, private investments are more likely to add complexity to your portfolio than improve performance.

The push into alternative or private assets can be laid at the feet of the late David Swensen, who used private equity and venture capital investments to great effect, juicing performance at Yale’s multi-billion-dollar endowment over several decades. Yet even Swensen, in his book Unconventional Success: A Fundamental Approach to Personal Investment, had a skeptical view of the whole enterprise:

Non-core asset classes provide investors with a broad range of superficially appealing but ultimately performance-damaging investment alternatives.

So, you’re probably asking, do I need private assets—equity, credit or real estate—in my portfolio? That’s a question that more and more investors will have to grapple with as they are faced with myriad new choices foisted upon them by an investment industry focused primarily on grabbing and locking up more and more of their clients’ assets.

Of course, they won’t exactly put it so bluntly. Couching it in the so-called “democratization of private markets,” investment firms are prying open the world of private investments—once reserved for endowments, pensions and the ultra-rich—for a broader pool of investors. Their ultimate vehicle of choice? Your IRA and 401(k), where assets are “sticky” and, when invested in private assets, will become even stickier.

And don’t think Vanguard isn’t in on this game. In an early interview upon becoming Vanguard’s CEO, Salim Ramji told Bloomberg that “low-cost investing applies in index, and it applies in active—and I would like it over time to also apply in private assets.”

True to his word, Ramji has steered Vanguard further toward offering private investments to its shareholders. They recently announced a partnership with Wellington and Blackstone and the upcoming launch of the WVB All Markets interval fund.

Of course, Vanguard is not alone.

- Capital Group (the outfit behind the American Funds) launched two interval funds with KKR (see here and here) that include investments in public and private bonds.

- State Street’s new SPDR SSGA IG Public & Private Credit ETF (PRIV), launched in collaboration with Apollo Global Management (one of the largest private investment firms), stuffs private credit into an ETF. The two firms have also partnered on a target-date fund series geared to retirement accounts that allocates 10% of assets to private investments.

- The 401(k) servicing giant Empower is teaming up with seven firms to allow private assets into some of their clients’ retirement accounts later this year—see here.

As the rush to offer and sometimes push private markets onto unsuspecting investors picks up speed, now is a great time to educate yourself on their ins and outs and understand the reasons the fund industry is getting behind “democratization” with such energy.

Before I go on, let me put my cards on the table: I’m highly skeptical of most private investments. If you can somehow gain access to top-tier managers, it may be worth a go. But those managers are few and far between, often have no room for the little guy, and aren’t in any need of your dollars or mine. Otherwise, private investments just add complexity and fees while reducing transparency and liquidity—all without improving results or reducing risk.

So, my very short answer to the opening question is: No, you don’t need private investments in your portfolio.

Why the Push?

Before delving into what private investments are all about, it's worth asking, “Why now?” Why are private asset managers opening the gates to make their strategies and funds more widely accessible?

As I noted, the proponents of this push will tell you it is about “democratizing” access—giving smaller, everyday investors a seat at the table that was previously reserved for institutions and the wealthy. Their pitch, in a nutshell, is that everyone should have access to investments that can reduce risk and boost returns. It sounds very altruistic, right?

The more realistic response is that investment firms are searching for ways to grow. They’ve apparently tapped out the pocketbooks and wallets of their institutional and high-net-worth customers and are now looking down-market for growth.

To give just one example, the NACUBO-Commonfund Study of Endowments found that the average institution allocates 55% of its portfolio to private assets, such as real estate and “alternative strategies.” That’s a lot, and it implies that institutions are probably maxed out on private investments.

Hello, mom and pop!

Private Markets 101

The short definition of a private investment or asset is that it does not trade on a public exchange, like the NASDAQ or the New York Stock Exchange. To give an Elon Musk-driven example, Tesla is a public company, but SpaceX is private. Anyone with a brokerage account can trade Tesla’s stock all day long, but good luck trying to do the same with SpaceX.

(Yes, SpaceX shares are available to investors, but only the very wealthy who have access through some external “guardian.” In fact, you can find SpaceX shares held by a few public mutual funds. But those are few and far between.)

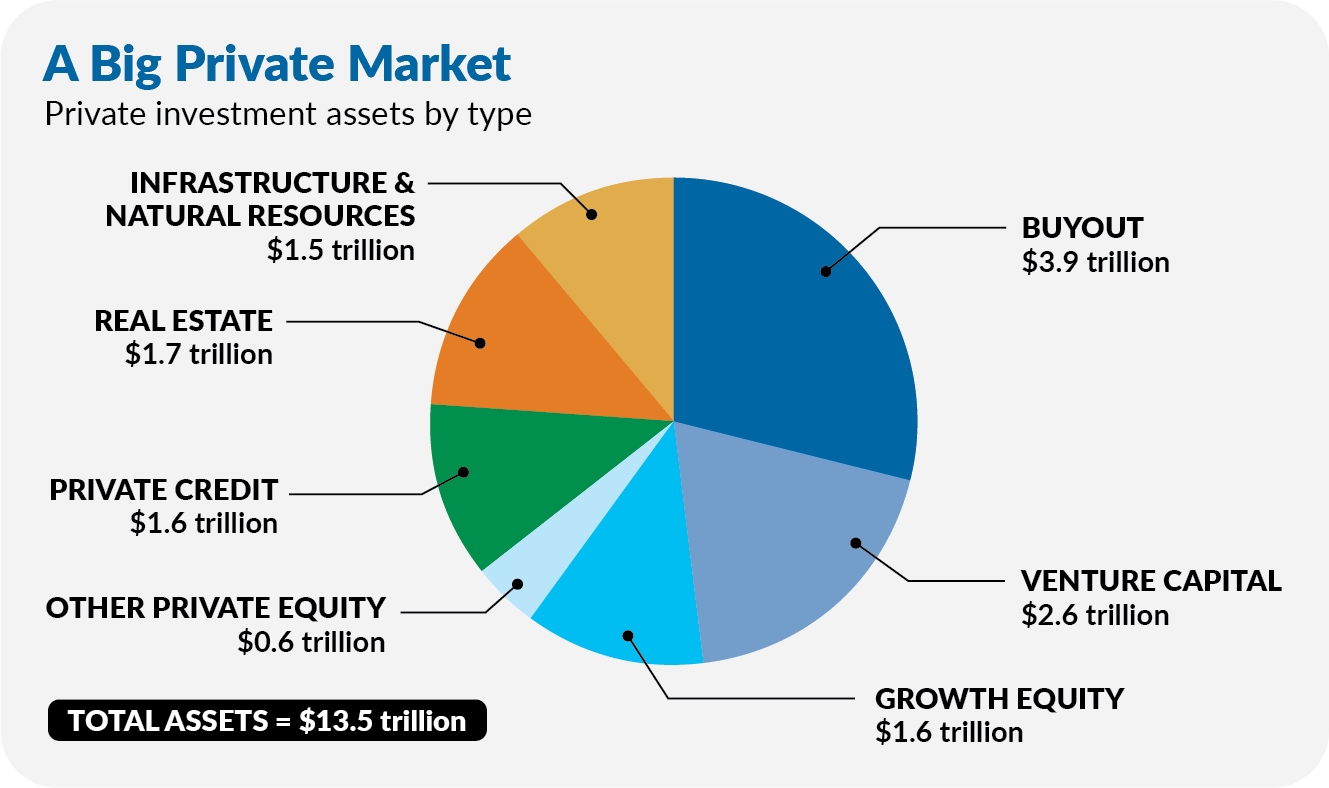

Private markets cover a wide range of assets, not just stocks. They include private debt (loans to private firms), real estate not wrapped in a REIT, and infrastructure and natural resources (like airports, toll roads, farmland, and timber). And “private equity” is a catch-all term for several different private investment strategies, like venture capital, leveraged buyouts and growth equity.

Here are brief and simplified definitions of the different types of private assets or investments:

Private equity: Buying all of or part of a company that is not listed on a public stock exchange.

Private credit: Lending money directly to companies (or consumers), bypassing traditional banks without aggregating that debt into publicly available securities such as bonds.

Private real estate: Buying and managing physical properties like hotels, resorts, offices, apartments, warehouses or data centers.

Private infrastructure & natural resources: Investing in essential assets like utilities, roads, bridges, airports, farmland or mineral rights.

Whether it’s private equity or private credit or any of a host of other terms, these investment options tend to come together under the heading of “alternatives.”

According to Vanguard (here), the alternatives market comprised nearly $14 trillion by late 2023; that number has almost certainly risen in the past 18 months or so.

For context, the public U.S. stock market (measured by the Wilshire 5000 Index) is $56 trillion in size, and the U.S. Treasury market alone is nearing $30 trillion. At $14 trillion or even $15 trillion, the private investment market is big but nowhere close to as big as the public markets.

Private equity accounts for roughly two-thirds of the private market universe. It’s also the one investors are most familiar with, so let’s start there. The easiest way to understand it is by comparing it to a stock mutual fund.

In the public markets, a mutual fund manager or index-fund provider buys stakes in publicly traded companies. Typically, they are forced by law not to exceed certain ownership limits. By contrast, the private equity manager, called a general partner, has the ability to buy entire companies or controlling stakes in private companies.

Fees differ, too. Mutual funds usually charge a single annual fee. At Vanguard, these fees (on non-institutional share classes) range from 0.03% to 1.40% of the assets under management. The only fund charging over 1% per year is Market Neutral (VMNFX).

Private equity managers are much better paid (meaning you pay a lot, lot more): They commonly charge a 2% annual management fee plus 20% of any profits they generate.

Some private equity managers may charge less, but others can and do charge more. In fact, unlike Vanguard, which has lowered fees as it has become more successful, the best private equity managers often raise fees as their reputations grow.

Mutual funds are open-ended—you can buy and sell shares daily. Sometimes fund companies (like Vanguard) will close a fund to new investors, while still allowing you to cash out at any time. And unless the fund is merged or liquidated, there’s no set end date. The fund operates in perpetuity.

Private equity funds work differently. They raise money in a lump sum (a fixed pool of capital), then spend the next several years using that money to make their investments. (Technically, the private equity funds don’t ask for all the cash up front, but will “call” your money over time as they make their deals.) Once the acquired companies (ideally) grow or become more valuable, the private equity fund sells them—either to another private investor or through a public stock offering.

Three Flavors of PE

Not all private equity managers target the same types of companies. Broadly speaking, private equity falls into three main styles:

Venture capital focuses primarily on buying pieces of early-stage startups and smaller private companies with high growth potential. Most of these companies go bust or simply meander along, but the rare success stories can deliver outsized returns when sold.

Leverage buyout (LBOs) involve acquiring mature companies, often using money borrowed against the company’s assets. Hopefully the company’s cash flow can cover the debt expense while the borrowed cash is used to boost the company's value through operational changes—cutting costs, restructuring leadership, refinancing debt or taking on even more debt to fund expansion.

Growth equity takes a middle path. Managers invest in established, profitable businesses by buying a minority stake. These companies don’t need a turnaround—they need capital to grow. Success (or failure) is often uncertain for years.

Investors in private equity funds typically see their money returned gradually as the funds sell their holdings. Most private equity managers aim to fully exit their investments within seven to ten years. As a limited partner—an outside investor in the fund—your capital is locked up for the duration, with limited or no access to it until those sales happen. And if the fund’s investments crater, or simply muddle along, you could see a poor return, or no return at all.

By contrast, very few mutual fund investors have seen their money disappear. The reason: Mutual funds are typically much more diversified than a private fund and are priced daily. This gives the shareholder visibility into any troubles and the ability to sell out well before net asset values fall to zero.

Even if your private equity fund communicates that its investments are lagging, you have no recourse—you must “stay the course” even if it brings you onto the rocks.

Private equity firms raise money every year (or every few years) to create new funds, creating different “vintages.”

This is the “classic” private equity fund structure, and it’s how Vanguard’s private equity funds, launched in partnership with HarbourVest, have been set up.

For the most part, Vanguard’s HarbourVest funds have only been available to institutions and wealthy investors meeting regulatory definitions of “qualified purchaser” or “accredited investor.” Vanguard raises the bar high: You need at least $5 million in Vanguard assets, in addition to meeting those definitions, to invest in Vanguard’s private equity funds.

Private credit and real estate funds tend to be a little different from private equity funds. In particular, they are usually “evergreen,” meaning they don’t have an end date. With no end date, the managers will typically allow investors to withdraw some of their money periodically, but within tightly controlled limits. That said, private credit and real estate funds typically pay monthly or quarterly income, so investors see some return more quickly.

In recent years, some private equity firms have launched evergreen funds as well.

Regardless of the structure, the core principles for all private investment funds are the same: The private fund manager raises a limited amount of money from a limited client base. They use that money to buy illiquid, private assets before returning any profits to investors years later. Oh, and while you wait, investors pay a hefty fee and ultimately give up a decent share of any profits for the privilege.

With that background, let’s dig into the arguments for and against investing in private markets. To keep it simple, I will focus my comments on private equity. Much of what I have to say about private equity applies to private credit and real estate, and before we wrap up, I’ll add a few specific comments on those strategies.

The Performance Debate

The argument for adding private equity to a portfolio goes like this: By locking up your money and investing in less efficient private markets, you can earn higher returns than from simply buying and holding, say, 500 Index (VFIAX). But it gets even better: Those higher returns are also less volatile than and are uncorrelated with your traditional public stock holdings.

Thinking critically about the less volatile and uncorrelated return claim is important, but the promise of earning higher returns is what really draws investors to private equity. So, let’s start with a seemingly simple question:

Does private equity outperform an investment in a low-cost index mutual fund (or ETF)?

Spend some time on the internet and you can certainly find plenty of examples that suggest that yes, private equity does indeed outperform.

For example, the table below compares the returns of an index of private equity funds created by Cambridge Associates (an investment firm advising endowments, pension plans, foundations, etc.—in other words, a heavy user of private funds and investments) to several public stock indexes. Based on these numbers, private equity outperformed on average by around 5% per year!

"Evidence" That Private Equity Outperforms

| 5-year | 10-year | 15-year | 20-year | 25-year | |

| CA US Private Equity Index | 17.0% | 15.4% | 17.0% | 14.6% | 13.0% |

| MSCI All Country World Index | 11.8% | 9.6% | 12.7% | 8.4% | 7.4% |

| Russell 300 Index | 14.7% | 12.5% | 16.2% | 10.3% | 9.0% |

| Russell 200 Index | 8.5% | 7.8% | 14.4% | 8.5% | 8.7% |

| Note: Data as of 3/31/2024. Private Equity Index returns are "pooled horizon internal rate of returns." Public index returns are "modified public market equivalent (MPME) returns. | |||||

| Source: Cambridge Associates and The IVA | |||||

However, before considering this case closed, remember that private equity fund reported returns must be taken with a huge grain of salt. Here’s what Vanguard had to say in a November 2019 report, Private equity: Assessing its role in a nonprofit portfolio: “[W]ith estimated and subjective asset valuations, the lack of objective robust benchmarks, less transparency, and extended time horizons, evaluating performance is a more taxing and less precise exercise.”

By the way, that 2019 report seems to have conveniently disappeared—or at least, I couldn’t find it on Vanguard’s website. If I missed it, let me know. In the meantime, I’ve attached a copy I saved six years ago:

You may have noticed in the fine print of the table comparing Cambridge Associates’ private equity index to public stock indexes that private equity index “returns” are actually “internal rates of return” (or IRRs). To be clear, an IRR is not like the usual return figure for mutual funds; it’s a calculation meant to reflect the timing of money going into and out of the portfolio.

Cambridge has adjusted the public index fund returns to account for the flows into and out of the private equity funds. The resulting “modified public market equivalents” are quoted in the table.

Obviously, this isn’t as clear-cut as when we are comparing two mutual funds or ETFs. Also, let’s not forget that Cambridge Associates’ private equity index isn’t an index like the S&P 500. You can’t go out and invest in all the private funds that populate the “index.” So, take the table and its comparisons with a big grain of salt.

Additionally, while I’ve found some data suggesting that private equity outperforms, I’ve also read plenty of research suggesting it doesn’t. For example, Ludovic Phalippou’s 2020 paper, An Inconvenient Fact: Private Equity Returns & The Billionaire Factory, details how “Private Equity (PE) funds have returned about the same as public equity indices since at least 2006.”

Phalippou also notes that “More people have obtained access to other comprehensive datasets. Highly respected and visible academics … have reported what they found: average PE net returns in line with public equity returns.”

So, what are we to make of the conflicting evidence?

Vanguard’s Verdict

Vanguard seems to buy into the premise that private equity outperforms. In a November 2023 report, The case for private equity at Vanguard, the authors say, “Vanguard expects a broadly diversified PE program with exposure to top-performing managers to outperform global equities by 350 basis points at the median.”

Outperforming by 3.5% per year sounds good. But why is Vanguard using global stocks as the hurdle? Most private equity funds buy U.S. companies. Plus, an investment in 500 Index outperformed Total World Stock Index (VTWAX) by 3.9% over the past 15 years—12.9% to 9.0%. Suddenly, that 3.5% hurdle doesn’t sound so impressive.

Also, note that Vanguard’s expected outperformance is predicated on having “exposure to the top-performing managers.” That’s easier said than done. And, as I’ll show in a minute, who you invest with is even more important when picking a private equity fund than when selecting a mutual fund.

The IVA Verdict

Here’s what tips the scales toward healthy skepticism for me. If private equity truly outpaced public markets, I’d expect college endowments, which, as we established, are loaded up on private funds, to outperform their peers and the market consistently and by a meaningful amount.

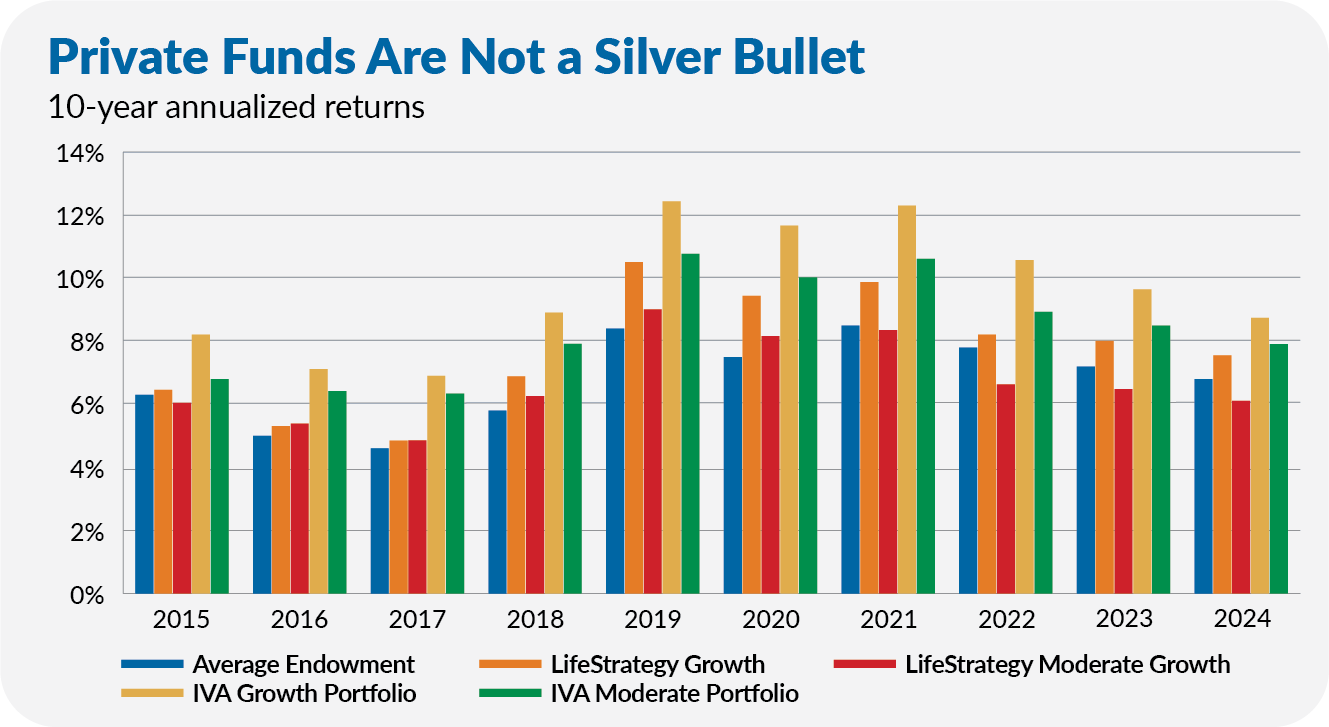

But they haven’t. As you can see in the chart below, college endowments have not, on average, done better than Vanguard’s simple index-based strategies or our IVA Portfolios. I included a few different comparison points because while a 60%/40% stock/bond portfolio is a common benchmark for endowments, most run with far less invested in bonds.

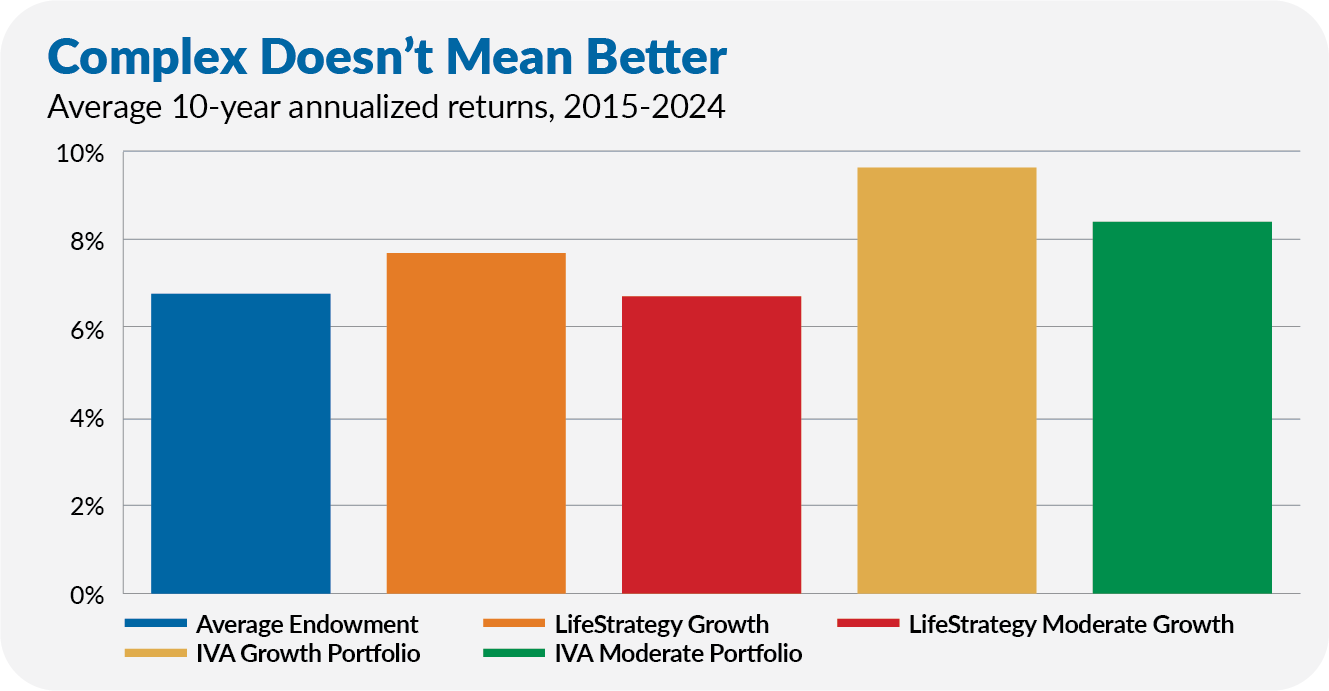

Or, to make it easier, the following chart shows the average of those 10-year annualized returns for the endowments, Vanguard funds and IVA Portfolios.

Again, if private equity led to public-market-beating returns, you’d expect the average endowment to top this podium. It doesn’t.

Fewer Trades ≠ Less Risk

So, how about the other benefits of private equity—lower volatility and correlation? Put simply, these are more illusion than fact.

Private equity’s lower volatility and low correlation to public stocks stems from the fact that you simply can’t price a private-equity investment every day or even every month. The value of your home rises and falls through time but is only apparent when a sale occurs. The same can be said for the holdings of a private-equity fund.

Contrast this with a mutual fund, which is priced every day based on the value of its holdings. The values of those holdings are (for the most part) determined by a vast public market that itself is priced daily—transparency is high.

Frankly, the valuations put on private companies in the portfolios of private equity funds raise a tremendous conflict of interest. Because private-equity firms charge a fee on assets, their general partners, who take those fees home, want to value their holdings as highly as possible. Yes, third parties and guardrails exist to help mitigate this conflict, but it still exists. And transparency into valuations is virtually nonexistent.

Not to muddy the distinction, but let me use an example from the mutual fund world to show how valuing a private company isn’t always straightforward.

Various Fidelity and Baron funds co-invested alongside Elon Musk to take Twitter (now X) private in late 2022. As the venerated Allan Sloan documented late last year, for most of 2023, the two mutual fund companies put very different values on their shares of this private company. While Fidelity had marked its holdings down some 60%, Baron only thought the value had dropped 20%–30%. (Eventually, Baron lowered its estimate to roughly match Fidelity’s valuation.)

Once again, Vanguard is on the cheerleading side of this debate, arguing in an October 2023 research paper, The diversification benefits of private equity, that you should invest in private equity to better diversify your portfolio.

I'm sorry, but their analysis contradicts the conclusion.

First, in the paper, Vanguard acknowledges that “the fundamental drivers of cash flow production—and, ultimately, returns to shareholders—are very similar between public and private companies.” Second, the authors use a correlation of 0.9 (which is very high) between private equity and public stocks when running different hypothetical portfolios through their models.

In other words, you aren’t diversifying your public equity portfolio by buying private equity.

More to the point, this makes no sense! No one is going to tie up their money for a decade (or longer) to improve diversification. You only lock up your money if you think you'll earn a higher return.

Don’t let the low volatility and correlation stats fool you. As The Wall Street Journal’s Jason Zweig recently put it, “assets that don’t trade every day aren’t low risk just because they don’t trade every day.”

Dramatic Dispersion

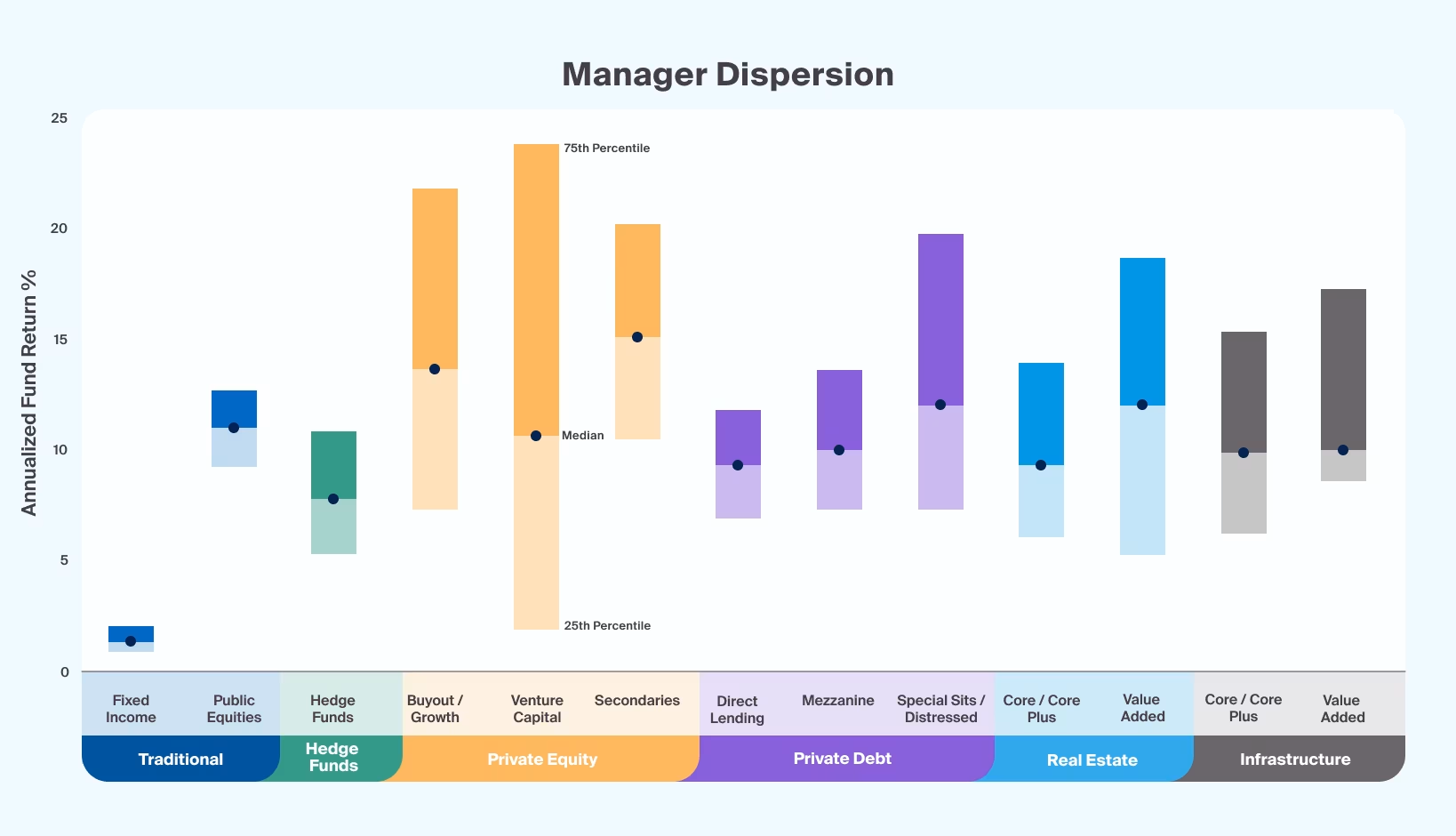

The last, but far from the least important, performance topic to discuss is the huge dispersion of returns among private-equity funds. (As you’ll see in the chart below, this issue applies to all private investment strategies.)

The chart below comes from CAIS Group, which runs a platform that enables financial advisors to access alternatives for their clients. It shows the dispersion of 10-year annualized returns for private equity, credit, real estate and infrastructure funds and traditional mutual funds.

Again, we’re not comparing apples to apples here. The private fund returns are IRRs, which shouldn’t be evaluated directly against mutual fund returns. But what I want you to focus on is how tall the bars are. The taller the bars, the greater the difference between the best and worst performers.

Yes, the top private-equity managers have delivered some attractive returns, but you could drive an entire convoy of 18-wheelers between the top quartile and bottom quartile managers. Even the spread between the best and the “average” manager is extremely wide.

Another way to look at it is that if you picked a bottom-quartile mutual fund (the “Traditional” category in the chart), you trailed the market by a little. If you owned a bottom-quartile private equity fund—and one out of four investors did—you probably never wanted to hear the words “private equity” or “alternative” again. Even a private equity fund that landed in the middle of the pack probably didn’t meet investors’ expectations (or hopes).

The bottom line here is that if you can’t invest with the best private-equity managers, then you shouldn’t invest in private equity at all.

David Swensen, the chief investment officer for the Yale Endowment and the man I mentioned at the onset who pioneered the extensive use of private-market investments in college endowments, put it this way: “Even if a [private-equity] index existed, based on past performance, index-like returns would fail to satisfy investor desires for superior risk-adjusted returns. In fact, only top-quartile or top-decile funds produce returns sufficient to compensate for private equity’s greater illiquidity and higher risk.”

The obvious question then is, can you be assured of investing with the top managers?

Too Big, Too Expensive, Too Exclusive

The simple answer is no, you can’t invest with the best. And you should be extremely skeptical that any private equity fund willing to take you on as an investor will be a top performer. In part, it comes down to math—only one out of four will, by definition, land in the top quartile.

But, more importantly, the best managers try to maintain a certain size and, because they are the best, get to choose who invests with them.

Here’s how Vanguard put it in its 2019 Private equity report: “Success breeds success, but that has its downside. When a manager achieves superior performance they attract more assets ... possibly dampening returns ... [T]he same successful manager who attracts more assets may choose to limit investments and only partner with select investors.”

In my view, this issue of scale—more assets leading to lower returns—applies to private equity at large. Though the performance metrics are dubious, even if private equity has outperformed public stocks in the past, you have to wonder if that will continue when the funds find their way into our 401(k)s and money floods into the space.

Which leads to the question of fees. I don’t think anyone disagrees that investing in private equity is expensive. As Vanguard said in its 2019 Private equity report, “There are two things that ring true about the costs of investing in [private equity]: The fees are difficult to understand ... and they are high.”

I know Salim Ramji told Bloomberg he would like low fees to apply to private investing, but unless Vanguard starts its own internal direct private investing division, I’m skeptical that fees will come down soon.

If you’re seeing more demand for entry into your fund than you’re willing to accommodate, or if money is pouring into private funds in general, what incentive is there to lower fees?

Vanguard seems to share my skepticism. In a recent podcast, Vanguard alum Karin Risi talked about accessing private equity and credit at a “fair price,” not a low price.

Or consider this very un-Jack-Bogle-sounding section from Vanguard’s 2023 report The case for private equity at Vanguard, “There’s no doubt that private equity fees are higher than public market fees; however, asset owners deciding on any investment or its manager should focus on net outcomes, not only fees or gross returns.” [Emphasis added.]

Let me share a few additional thoughts before wrapping up.

Structure Matters

As more private investments make their way into “retail” products, think very carefully about how the fund is structured. In particular, consider the liquidity (how easy it is to trade) of the underlying investments versus the fund itself.

Pouring illiquid investments into a daily liquid mutual fund is a recipe for disaster for fund shareholders. This is why the interval fund structure, which limits withdrawals, is better suited for private assets than daily liquid mutual funds.

I’m also very leery of private investments in ETFs—like State Street’s IG Public & Private Credit ETF. Yes, most ETF trading occurs between shareholders and doesn’t impact the fund. But at the end of the day, ETF portfolios are still meant to be daily liquid even if they hold illiquid assets. (Plus, given the fund currently sports an SEC yield of 4.7%, barely higher than what you can get from Treasurys, I don’t see the appeal.)

Beware Chasing Private Credit Yields

Assets in private credit funds have grown by leaps and bounds lately as investors flock to their (sometimes) higher yields. But remember this fundamental rule of the bond market: You only earn a higher yield by taking on greater risk.

At the end of April, the 10-year Treasury’s yield was 4.2% and High-Yield Corporate (VWEHX) was yielding 6.6%. To use one popular private debt fund as an example, Blackstone’s Private Credit (BCRED) reports an annualized distribution rate of 10.5%. (High-Yield Corporate’s distribution rate was 6.5%.)

Do you think that BCRED’s double-digit yield, which is 4% higher than Vanguard’s junk bond fund, comes without risk? No. It comes from lending to riskier borrowers and using leverage (or borrowing against the fund’s portfolio to invest in even more private loans).

I know many private credit funds will tell you they are lending to high-quality borrowers. Heck, Blackstone describes BCRED as having a “defensive portfolio position” and claims to invest in “high-quality companies.” However, the footnote on that last claim says the fund “will generally invest in securities or loans rated below investment grade or not rated which should be considered to have speculative characteristics.” I’m not sure how they get away with that.

I’m not out to pick on Blackstone. But as a big player in the market who is in a strategic partnership with Vanguard, they are a ready example and worthy of some scrutiny.

The bottom line is that borrowers and the bond market aren’t dumb. If the companies borrowing from private credit funds could borrow at lower rates, they would. As I said, a higher yield is a sign of greater risk.

Where Private Makes Some Sense

Of all the private assets available or becoming available to more investors, I find real estate, infrastructure and natural resource strategies the most intriguing for two reasons.

First, as I’ve discussed, publicly traded real estate investment trusts (REITs) are way more volatile than you’d think, given what they own—buildings. The private real estate interval funds I’ve analyzed are less volatile than Real Estate Index (VGSLX). Even if some of those lower volatility profiles are a mirage, the interval funds act and feel more like what I’d expect from owning real estate.

Second, assets like farmland, timber and infrastructure should actually diversify a portfolio of publicly traded stocks and bonds over time. You can find these assets in public markets, but your options are limited.

That said, you have to ask yourself if you really need to have those in your portfolio.

My Take: Complexity Isn’t a Winning Strategy

This brings us back to where we started—no, you don’t need private assets in your portfolio.

Private investments are an expensive, illiquid and complicated way to own stocks, bonds and real estate. They offer the potential for greater returns, but there is no guarantee you’ll do better with private investments and funds than you would in the public markets, where information, among other things, is much more transparent. And the potential is there for your investments to do a lot worse than the public markets. It’s a two-way street.

If you can somehow gain entry to the best private funds, you probably should consider a small investment there. But, as Vanguard wrote in their 2019 Private Equity research paper, “That performance, however, comes with extreme volatility at times, prolonged time horizons, illiquidity, lack of transparency, high fees and added layers of due diligence and operational complexity.”

I’ve said it before and will say it again: Complexity doesn’t generate better investment outcomes. Often, private funds add unnecessary complexity and uncertainty to a portfolio.

But don’t just take it from me. Take it from Swensen: “In the absence of truly superior fund selection skills (or extraordinary luck), investors should stay far, far away from private equity investments.”

I would extend that to all private investments.

Vanguard and The Vanguard Group are service marks of The Vanguard Group, Inc. Tiny Jumbos, LLC is not affiliated in any way with The Vanguard Group and receives no compensation from The Vanguard Group, Inc.

While the information provided is sourced from sources believed to be reliable, its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Additionally, the publication is not responsible for the future investment performance of any securities or strategies discussed. This newsletter is intended for general informational purposes only and does not constitute personalized investment advice for any subscriber or specific portfolio. Subscribers are encouraged to review the full disclaimer here.