Subscribers (new and old) often ask me which of my recommended Portfolios they should follow. It’s a quick question without a quick answer … because making that decision requires that you evaluate both your ability and your willingness to take on risk.

The decision about how much risk to take—how much to allocate between stocks and bonds and cash—is a fundamental decision that has a big impact on your long-term returns and your mental health.

I’ve read studies showing that asset allocation drives 70% to 90% of performance over time. And yet, investors spend far less time thinking about how much to allocate to stocks versus bonds compared to the amount of time and energy poured into selecting one fund over another.

Frankly, I am also guilty of spilling far less ink on this topic compared to fund analysis, so allow me to try and balance the scales a little. I’ll talk you through how I think about risk and help you figure out which of my different Portfolios is best for what you are looking to achieve with your investments. But before I do that, I’ll give you a few shortcut solutions—and tell you why you might want to take the longer way around.

It should go without saying that I’m talking about setting your portfolio up for the long run; short-term outlooks don’t factor in here. If I could reliably time the market’s ups and downs, then you and I wouldn’t have to worry about this—I’d simply tell you when to take risk (and therefore own stocks) and when not to (by holding cash).

Oh, if only it were so.

Now, here’s a fair warning: I am not going to give you “the” answer. My goal is to equip you with the tools that enable to you find an answer that is right for you.

Key Points

- Think about both your ability and willingness to take risk when deciding how much to allocate to stocks or bonds

- You can look to Vanguard’s Target Retirement funds and risk assessment tool for input, but each shortcut has its limitations

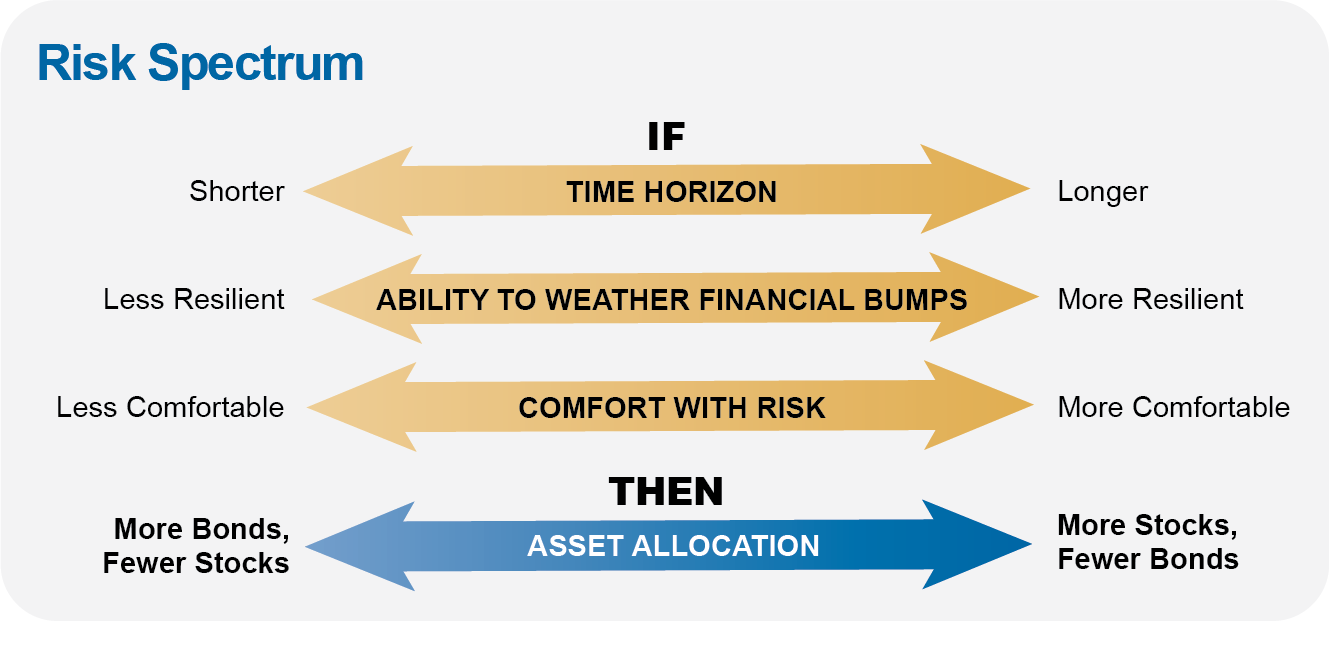

- The longer your time horizon, the stronger your financial position and the more comfortable you are with risk, the greater allocation to stocks you can handle

Spreadsheet vs. Real Life

First, let me quickly define some terms that are central to the risk conversation.

Your ability or capacity to take on risk is determined by your time horizon and your financial stability. The longer your time horizon and the stronger your financial foundation, the more easily you’ll be able to weather adverse events and still achieve your long-term goals.

Your risk capacity is fairly easy to evaluate—or at least relatively easy to punch into a spreadsheet. But we live in the real world, where spreadsheets are no use when it comes to emotions. So, the other part of the allocation conversation has to do with your willingness to take on risk. (Sometimes this is called your risk tolerance.) How much of a risk-taker are you? How far can your portfolio fall in value before you deviate from your investment plan?

I’ll take a closer look at these sides of the risk coin in a moment, but first let’s discuss two shortcuts to figuring out which Portfolio is right for you.

The Targeted Solution

If you want a real shortcut to deciding how much to allocate between stocks and bonds, it doesn’t get much easier than using Vanguard’s Target Retirement funds as a guide.

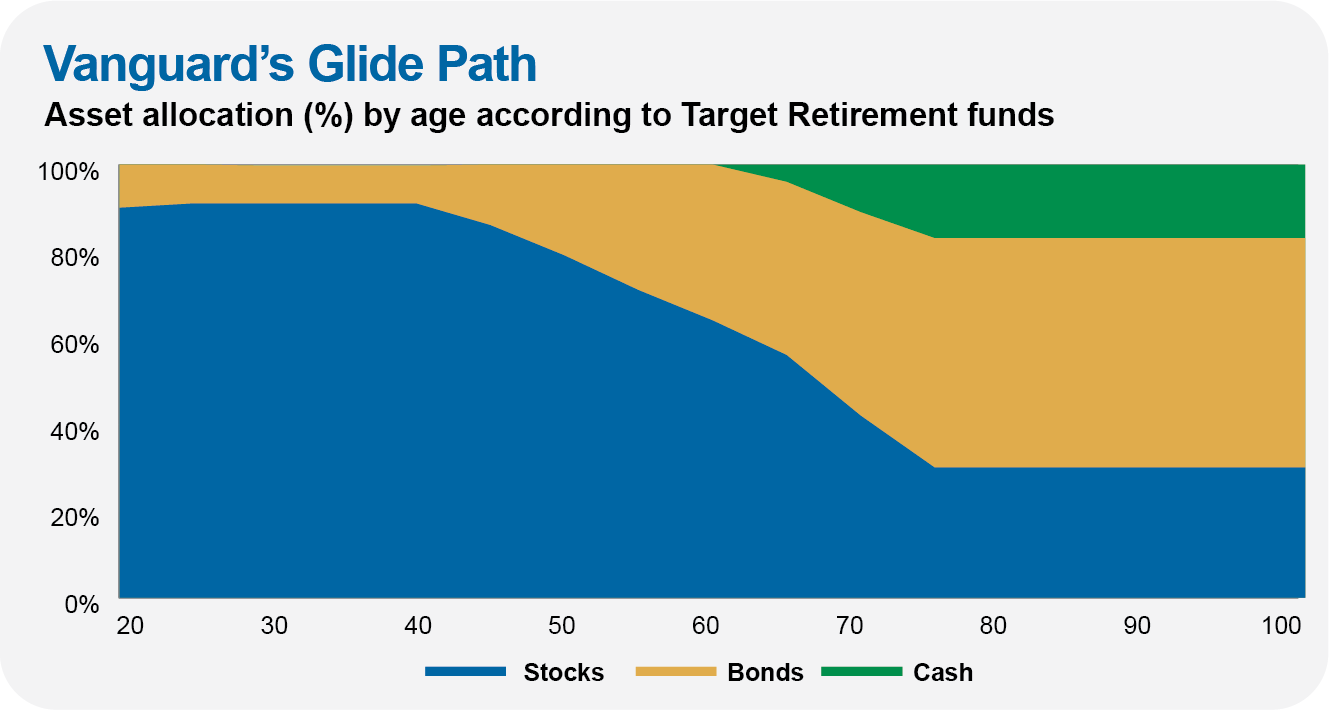

Vanguard has designed these funds to be the one fund an investor can own for life—not only up to retirement, but through it, as well. Each Target fund starts out heavily allocated to stocks (around 90%) and then slowly whittles that down over time. This declining stock exposure is called the glide path—you can see what this looks like in the chart below. Each fund moves down the glide path until it is merged into Target Retirement Income (VTINX), which becomes your “terminal” fund and allocation.

Vanguard recommends that investors in their 20s and 30s allocate 9 out of 10 dollars to the stock market. During your 40s and 50s, they suggest reducing your allocation to stocks, such that by the time you enter your 60s, about 65% of your portfolio is in stocks. Vanguard then advises cutting your stock exposure aggressively in the first decade of retirement. At age 75, you should have only 30% of your portfolio in stocks and keep it that way for the rest of your life, they say.

Again, that’s a guide to “lifetime allocation” according to Vanguard. If all you want is a shortcut for determining how to allocate your assets, pick the appropriate Target Retirement fund and follow its mix of stocks, bonds and cash.

It’s a shortcut, but not a particularly good one.

Think about it. The only variables in play here are your age today and your age at retirement—which Vanguard assumes is 65. I probably don’t have to tell you that there is a whole lot more to consider when it comes to setting your asset allocation than your age.

Don’t believe me? Just think about everyone you know who’s roughly your age. Are you all in the same financial situation? Do you earn the same income? Are all of you saving and spending the same amounts? Have you all had the same experience with money and wealth through time? Do you all have the same goals and definitions of success and happiness? What about family? Health? Of course you aren’t all the same. Age has almost nothing to do with it.

So, ask yourself: Why should we all automatically invest in the same portfolio, simply because we were born around the same time? You know the answer already: You shouldn’t.

Or, to give just one more example of how age is just a number, plenty of investors over the age of 75 are not only comfortable with having much more than 30% of their portfolio in stocks, they want it that way! Why? Because they aren’t investing for themselves, but for the next generation and beyond.

Vanguard Will See You Now

Another shortcut would be to complete one of the many “risk tolerance” questionnaires available on the web. You can find Vanguard’s here. (Or if you prefer it as a printable PDF, you can find that here.) Vanguard’s is 11 questions long and as good as the next, I guess. It focuses heavily on your time horizon and your comfort with risk (how you behaved in past bear markets) but doesn’t, in my opinion, fully tackle your ability to take on risk.

It's worth noting that when I took Vanguard’s assessment, they suggested I invest 80% in stocks and 20% in bonds. That’s less than what I would have in stocks if I owned my age-appropriate Target Retirement fund. So, you won’t necessarily get consistent advice from Vanguard!

While researching this article, I completed several other risk assessments. For example, I took this risk assessment from the University of Missouri (which is much more involved than Vanguard’s). I scored on the lower end of the “High” risk tolerance bucket. That feels about right … I’m capable of (and comfortable with) taking risk, but I don’t consider myself a big risk-taker. (I thought this was one of the better tests out there, but you’ve got to find one that works for you.)

As you may have figured out by now, all risk tolerance assessments should be taken with a big grain of salt.

And it gets complicated. For instance, are you answering the questions for your overall portfolio or just a portion of your investments? I don’t plan on touching my retirement accounts for decades, but the money in my brokerage account may be used for a down payment on a house in the next several years. I would answer a risk questionnaire very differently depending on which “bucket of money” I have in mind.

Also, keep in mind that these tests tend to take an average of your ability to take on risk and your willingness to take on risk when giving you a final score. I can make a very good argument that you shouldn’t average the two components but should follow the lower score, whichever that might be.

For example, say you are in great financial health—a reliable income, ample savings, a decent level of insurance, little debt and so on—but you hate seeing your portfolio drop dramatically in price. The risk assessment tools would probably tell you to hold a moderate portfolio (averaging your high capacity for risk with your low tolerancefor risk). But even a moderate portfolio might be too volatile for you to stomach, and it might result in you panicking out of your investments during the next bear market and then missing the inevitable bull market rebound.

Or, as another example, maybe you can stomach a lot of risk, but you have a short time horizon. Again, a risk assessment is probably going to recommend a moderate allocation … which could be a problem if a bear market strikes between now and your not-too-distant deadline.

When it comes to any risk assessment, don’t take the output as written in stone, but as a guide. If your portfolio is dramatically different, try to understand why.

It can also be useful to take one of these tests the next time falling prices and scary headlines have you thinking about bailing out of the market. Why? Because they force you to step back and think why you are investing in the first place.

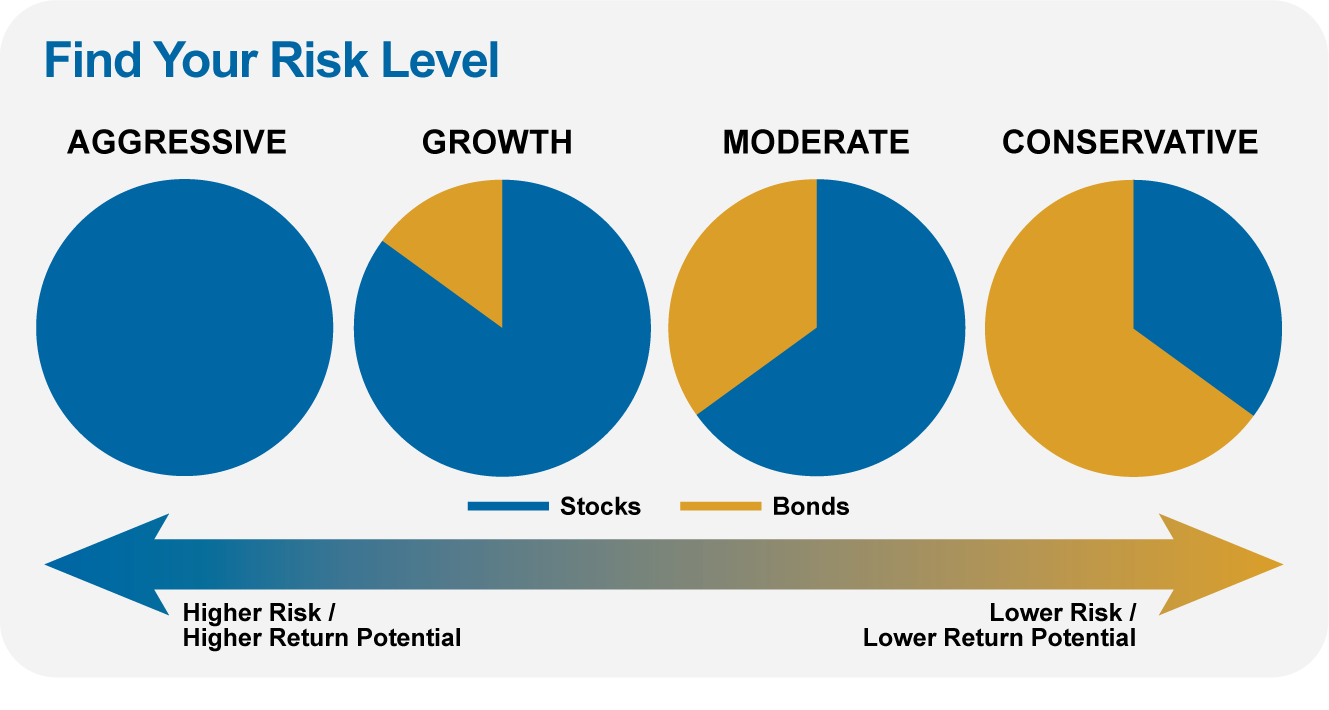

In the table below, I’ve listed the long-term allocation to risk assets (think stocks) for each of my Portfolios. Then, I mapped each Portfolio to the (flawed) shortcuts—Vanguard’s Target Retirement funds and the Missouri risk assessment. (If you use Vanguard’s risk tool, just pick the Portfolio with the closest equity allocation they suggest.)

| Portfolio | Stocks | Target Retirement | Uni. of Missouri Risk Level |

| Aggressive & Growth ETF | 100 | 2050-2070 | High (33-47) |

| Growth | 85 | 2040-2045 | Above-averge (29-32) |

| Moderate | 65 | 2025-2035 | Avg./moderate & below-avg. (19-28) |

| Conservative | 35 | 2020 & Retirement Income | Low (0-18) |

Talk about imperfect! As I hope I’ve made clear, don’t take these shortcuts too seriously—worse, I think they offer a false sense of precision. For example, if you score a 28 on the Missouri test, is that really different than scoring a 29 or a 30? Should it be the only reason you pick the Moderate Portfolio over the Growth Portfolio? No. Again, use these shortcuts as a sounding board at most.

Mapping My Portfolios

When it comes to my recommendations, I’ve tried to structure (and name) the Portfolios so that you can broadly identify each as appropriate for an aggressive or conservative investor without getting overly specific—this is a case where being roughly right is better than being specific but wrong. And, of course, you can always mix and match or tweak the Portfolios to your desired risk level.

So, how do you identify what type of investor you are and what’s an appropriate level of risk? Here are the questions I’d ask myself to answer that question.

Are We There Yet?

The first (and easiest) consideration is your time horizon. How long do you plan to have your money invested?

If you expect to spend the money in the next 12 to 24 months (and can’t make up a shortfall), then you should own cash—money markets, savings accounts, CDs. Maybe if you are willing to take on a bit of risk, you could go for Ultra-Short-Term Bond (VUBFX or VUSB) or Ultra-Short-Term Tax-Exempt (VWSTX). But even that may be too much for someone with a short time horizon between investing today and spending tomorrow.

If it’s money you’ll be spending in the next three to five years, then short-term and intermediate-term bonds are where you want to be. Beyond that, stocks can start entering the picture and should play an increasingly large role as your time horizon extends.

Why? Because stocks are volatile in the short run but have outpaced bonds and cash over the long run. When it comes to growing your wealth, you want to harness the compounding power of the stock market—but you have to give it time to work.

Riding Out the Bumps

The second puzzle piece is your ability to take on risk. How resilient is your financial situation?

Think of it like the suspension on your car. We all inevitably run into bumps on the road—these often take the form of large, unexpected expenses or bear markets. If you have a good suspension, the bumps aren’t so bad. If not, each bump threatens to knock you off the road.

As for the large, unexpected expenses, I’m not talking about your house burning down. Truly catastrophic events like that, well, that’s what insurance is for. Think of the smaller potholes we all hit—say, a $475 visit from the plumber. If that bathtub faucet starts leaking, do you have to turn to your investment portfolio or carry credit debt to get it fixed? (If so, you should take less risk.)

Or what about the next bear market (because there will always be another bear market)? If your investment portfolio declined 50% in value, would that impact your lifestyle? If so, you shouldn’t be all-in the stock market.

The resiliency of your financial situation comes down to the blocking and tackling of financial planning. Do you have an emergency fund? How much debt do you have? (And there’s a difference between credit card debt and a mortgage.) Do you have adequate insurance? If you are working, are you earning more than you spend, and how stable and reliable is that income?

If you’re in retirement, you probably still have some income (e.g. Social Security) but are likely to be spending more than you’re taking in. That’s okay, but how does your spending compare to the size of your portfolio? There’s plenty of debate about the efficacy of the old 4% withdrawal rule, and I will write an article on the topic down the road, but it still serves as a reasonable starting place. If you’re withdrawing around 4% of your portfolio (or less), that’s good. If you’re closer to 10%, well, that’s not sustainable.

Other than that (very) rough guidance on withdrawal rates, I’m not going to try and answer each of those questions because the answers are so situation-dependent. For example, how much insurance you need depends on whether you rent or own your home and whether you have children or not. The permutations are endless.

A Need for Speed?

The final consideration is the behavioral side of the coin—how comfortable are you with taking on risk? As I said, industry jargon calls this your “risk tolerance.”

If you’re a seasoned investor, the best way to assess this is to look at your behavior during past bear markets. Think back to the COVID bear market and the global financial crisis of 2008–09 (and the bursting of the tech bubble, if you were in the markets then). What did you do? Did you stay the course? Did you sell some (or all) of your stocks? Did you buy more?

Obviously, we are all allowed to learn and grow—just because you sold in 2008 doesn’t automatically mean you’ll sell in the next bear market. On the other hand, don’t kid yourself. If you’ve sold near the bottom in past bear markets, don’t load up on risk hoping you’ll do better next time.

If you’re just starting out and haven’t invested during a bear market, my advice is to take 90% to 95% of your portfolio and invest it in a low-cost, diversified portfolio … be it my Aggressive or Growth Portfolio or a dirt-cheap index fund (like Total Stock Market Index), or even one of Vanguard’s Target Retirement or LifeStrategy funds. Set up an automatic saving and investment plan—this may be through your 401(k), if you’ve got one. Your aim is to put in place the good habits that will serve you well over time.

My next piece of advice for a new investor is to take the remaining 5% to 10% of your portfolio and go buy what interests you—whether it’s tech stocks or gold or Bitcoin or whatever. You can learn a lot by making investment decisions and seeing the results—both good and bad. Think of this as your “learning” or “play” account. Hopefully, you will make some money, but if you lose money, that’s okay.

(You can skip the “learning account” if that doesn’t appeal. It just helps accelerate the process of discovering who you are as an investor.)

I had a learning account, and quickly realized that I’m not particularly “good” when it comes to buying individual stocks—it wasn’t that I didn’t make money (I did), but the stress level was too high. When I bought a stock, I was constantly checking its price and trying to decide what to do … not exactly good long-term investor behavior.

In contrast, when I bought a mutual fund that I’d done my homework on, it was much easier for me to buy and hold with confidence. I didn’t have a problem seeing my fund drop in price during the 2008–2009 bear market. I know I could stomach the risk of holding stocks, but for some reason, individual stocks were just more about trading than investing for me.

So, lesson learned: The best way for me to spend time in the market is by carefully selecting mutual funds and ETFs—not trading stocks.

The bottom line here is that we are not all built the same when it comes to risk-taking—and that’s okay. For some of us, the ups and downs of the stock market turn our stomachs. Others barely flinch no matter how volatile things get. What’s important here is being honest with yourself—it’s better to hold a more conservative portfolio through the market cycles than to try and “reach” for more returns in a portfolio that you won’t be able to stick with when markets turn south.

How Often to Change the Recipe

I also get the “how often should I change the stock and bond mix of my portfolio?” question. The short answer is: not very often.

Timing the market is impossible. This exercise has been about determining the risk level that you can hold through the ups and downs of the market while staying on course to achieve your goals.

It makes sense to check in annually and ask if your portfolio is positioned appropriately. However, you’ll want to keep short-term outlooks and recent market performance out of this assessment. So, most years—barring big life changes—you shouldn’t be overhauling your portfolio.

Putting It Together

I wish I could say, “give me these two data points and I’ll tell you exactly which Portfolio to follow.” Precision makes the risk assessment tools compelling but, well, life (and investing and the markets) is more like a Jackson Pollock painting than a work by Piet Mondrian. To make matters worse, our comfort with and ability to tolerate risk both change through time.

The graphic below should help you as you work through the questions I’ve asked throughout this article. Generally speaking, the longer your time horizon, the more resilient your current financial situation and the more comfortable you are with risk, the more you should allocate to stocks.

If you’re younger and just starting out, it can be daunting to “check all those boxes”—particularly when it comes to saving and debt. Frankly, when you are in your 20s or 30s, your time horizon is so long that it kind of trumps some of the other factors. Don’t feel like you have to check every box before you start investing—just get started. And when you do, focus on two things: Spend less than you make, and set in place the good behaviors and habits that will last a lifetime—automating your savings is the big one.

As you progress along your investment journey, the equation becomes more complicated. But don’t let that intimidate you. Take time to reflect on your current financial situation, how you’ve invested in the past and what you are trying to achieve in the future. Be as honest with yourself (and your investment partners) as possible, then act. If you need to adjust course down the road, you can always do that.

One of the hardest things to do in investing is finding what works for you and shutting out the rest. But if you can find a portfolio that keeps you in the market for the long haul, you’ll be a step ahead of the pack.