Executive Summary: While Vanguard may be a holdout now, more than 50 other fund firms want to offer ETF share classes for their traditional mutual funds—but the SEC hasn’t said yes (yet). As I believe it’s only a matter of time before Vanguard joins the fray, I break down the benefits, questions, and complications of this dual-share class structure, as well as what it could mean for fund investors.

UPDATE 6/11: A week after this article was published, Vanguard joined the growing list of fund companies asking the SEC for permission to add an ETF share class to its actively managed mutual funds.

Exchange-traded funds (ETFs) have been eating away at mutual funds’ dominance for years now. Legacy mutual fund companies are searching for a response. One solution they are eager to adopt is tacking an ETF share class onto an existing active mutual fund. The only problem? So far, regulators have said N-O.

However, the Securities & Exchange Commission, or SEC, is rethinking its stance. An IVA reader sent me a CNBC article reporting that with about 50-plus fund companies seeking SEC permission, the regulator is now “prioritizing the issue.” The IVA reader asked:

Is Vanguard one of the asset managers seeking the SEC’s approval to launch ETF share classes of its active mutual funds? Can you comment on this?

The first question is easy. So far, Vanguard has not asked the SEC for what is called “exemptive relief” to offer ETF share classes of its active mutual funds.

Of course, Vanguard could request permission at any time. They have tended to take a wait-and-see approach to significant changes in the industry before committing fully. But even if Vanguard doesn’t go down this road, ETF shares of actively managed mutual funds may be on the way.

ETFs 101

Starting at the beginning, what are exchange-traded funds (ETFs)?

The short story is that ETFs are mutual funds, typically index funds, that you can trade like stocks throughout the day—think of them as mutual funds version 2.0. It should come as no surprise that in developing version 2.0, the Wall Street wiz-kids made some improvements.

ETFs’ purported advantages are increased liquidity (you can trade throughout the day), transparency (their portfolios, for the most part, are updated daily) and tax-friendliness.

I’ll give ETFs the nod over mutual funds in terms of transparency and tax-friendliness. However, the ETF’s intraday trading feature is a questionable benefit. It may be advantageous for some investors, but it can be a losing proposition for others, particularly those accustomed to trading mutual funds at their net asset value (NAV) at the end of each day, as it adds complexity.

Still, ETFs have become exceedingly popular, so you can see why mutual fund companies are eager to find a way to incorporate the ETF model.

Why Are ETF Share Classes Hot?

As I mentioned, ETFs have been taking market share from mutual fund companies for years. Part of the explanation is investors' shifting preference for ultra-low-cost index offerings. ETFs are often the cheapest way to invest in an index—sometimes even cheaper than Vanguard’s index funds.

However, another attraction is that ETFs are perceived as a “better” fund structure than mutual funds—particularly when it comes to taxes. Investors are tired of mutual funds kicking out big capital gains year after year, so they are turning to ETFs, which rarely distribute capital gains.

Adding ETF share classes to existing actively managed mutual funds won’t solve the problem of investors favoring index funds, but it could solve the tax issue. The dual mutual fund–ETF share class structure could remove one objection to owning actively managed funds (at least in taxable brokerage accounts).

Mutual fund companies are also motivated by their bottom lines. If you are, say, T. Rowe Price, you want your mutual funds to be broadly available on different platforms—Fidelity, Schwab, E*TRADE, Vanguard, etc. However, T. Rowe Price pays a hefty fee (usually a percentage of the fund’s expense ratio applied to assets held at the platform) for shelf space for its mutual funds.

(Note: Vanguard does not do this, so you typically have to pay a transaction fee when buying a Vanguard mutual fund on the “other” platforms.)

ETFs, which are listed on the stock exchanges, don’t face those tolls. You can buy them through virtually any U.S. brokerage account. So, an asset manager would get to keep a larger cut of their ETF expense ratios than they would for a mutual fund, even if they are share classes of the same fund.

In other words, follow the money!

Of course, the dual mutual fund–ETF share class structure already exists in one place: Malvern, PA.

Vanguard’s Unique Position—and Its Limits

Yes, Vanguard already has ETF share classes for some of its mutual funds. However, this only applies to Vanguard’s index mutual funds.

In 2000, the SEC gave Vanguard permission (exemptive relief) to create ETF share classes of its open-end index funds. Thanks to their unique dual share class structure, Vanguard's index mutual funds have the same tax benefits as any ETF, as I showed you here.

However, the SEC's exemptive relief did not apply to Vanguard's active mutual funds. In fact, the SEC denied Vanguard's 2015 request that the relief be expanded to cover its active funds. (And, again, Vanguard isn’t currently asking for approval, though they did 10 years ago.)

So, here’s the state of play at Vanguard:

All of Vanguard’s index mutual funds have ETF share classes attached to them. However, not all of Vanguard’s index-based ETFs offer mutual fund shares.

None of Vanguard’s actively managed mutual funds offer ETF shares. However, that doesn’t mean Vanguard is entirely passive when it comes to ETFs. Here’s a list of the 11 actively managed Vanguard ETFs:

- Core Bond ETF (VCRB)

- Core Tax-Exempt Bond ETF (VCRM)

- Core-Plus Bond ETF (VPLS)

- Short Duration Bond ETF (VSDB)

- Short Duration Tax-Exempt Bond ETF (VSDM)

- U.S. Minimum Volatility Factor ETF (VFMV)

- U.S. Momentum Factor ETF (VFMO)

- U.S. Multifactor ETF (VFMF)

- U.S. Quality Factor ETF (VFQY)

- U.S. Value Factor ETF (VFVA)

- Ultra-Short Bond ETF (VUSB)

If you’re counting, that’s five factor ETFs, four taxable bond ETFs and two municipal bond ETFs. (Also, a fifth actively managed taxable bond ETF, Government Securities ETF, is due to launch in July.)

It does get confusing, though, because several of Vanguard mutual funds have essentially the same name as some of the ETFs on the active list. In particular, I’m thinking of:

- U.S. Multifactor (VFMFX) and U.S. Multifactor ETF (VFMF)

- Ultra-Short-Term Bond (VUBFX) and Ultra-Short-Term Bond ETF (VUSB)

- Core Bond (VCORX) and Core Bond ETF (VCRB)

- Core-Plus Bond (VCPIX) and Core-Plus Bond ETF (VPLS)

To be clear, despite similar names, the mutual funds and ETFs are technically separate entities. Therefore, the actively managed mutual funds do not share the tax benefits of the actively managed ETFs.

In the IVA Performance Review tables, I group these funds and ETFs together (as if they were share classes of the same fund) because Vanguard aims to make their portfolios nearly identical so that they perform similarly. So far, it has delivered.

In short, when it comes to actively managed ETFs, Vanguard has kept the ball moving on the bond side of the shop, but has stood still on the stock side since launching the factor ETFs in 2018.

Wait and See

To be clear, despite similar names, the mutual funds and ETFs are technically separate entities. Therefore, the actively managed mutual funds do not share the tax benefits of the actively managed ETFs.

In the IVA Performance Review tables, I group these funds and ETFs together (as if they were share classes of the same fund) because Vanguard aims to make their portfolios nearly identical so that they perform similarly. So far, it has delivered.

In short, when it comes to actively managed ETFs, Vanguard has kept the ball moving on the bond side of the shop, but has stood still on the stock side since launching the factor ETFs in 2018.

Dual Share Classes and Investors

Despite the hype, ETF shares of actively managed funds are far from the slam dunk many commentators and fund companies make them out to be.

What’s to Like: Lower Costs and Broader Access

First, an ETF share class should lower fees for investors.

In the four places where Vanguard runs similarly named but legally separate mutual funds and ETFs, the ETFs charge essentially the same expenses as the mutual funds’ higher minimum Admiral share classes, which are lower than the more accessible Investor share expenses. So, if that’s any guide, the ETF shares will save smaller investors money. That’s a win.

| Investor Shares | Admiral Shares | ETF | |

| Ultra-Short Bond | 0.20% | 0.09% | 0.10% |

| U.S. Multifactor | – | 0.18% | 0.18% |

| Core Bond | 0.20% | 0.10% | 0.10% |

| Core-Plus Bond | 0.30% | 0.20% | 0.20% |

Vanguard investors with non-Vanguard brokerage accounts also stand to save money from the dual mutual-ETF share class structure, since Vanguard limits the availability of its Admiral shares on competitors’ platforms. Plus, with an ETF, you can avoid the transaction fee those platforms charge when you trade Vanguard’s mutual funds.

If you want to buy, say, PRIMECAP’s Investor shares through your Fidelity brokerage account, you’ll have to pay a $100 transaction fee. However, most platforms do not charge transaction fees to trade ETFs. So, if PRIMECAP ETF was an option, you could purchase it at Fidelity without paying a transaction fee.

Of course, this assumes that the brokerage platforms don’t “respond” and change their fee structures.

Will the Tax Benefits Materialize?

Many investors hope that the dual share class structure will finally resolve the issue of actively managed mutual funds distributing large capital gains every year. I’d love to see that happen—but I’ll believe it when I see it. Here’s why I’m skeptical:

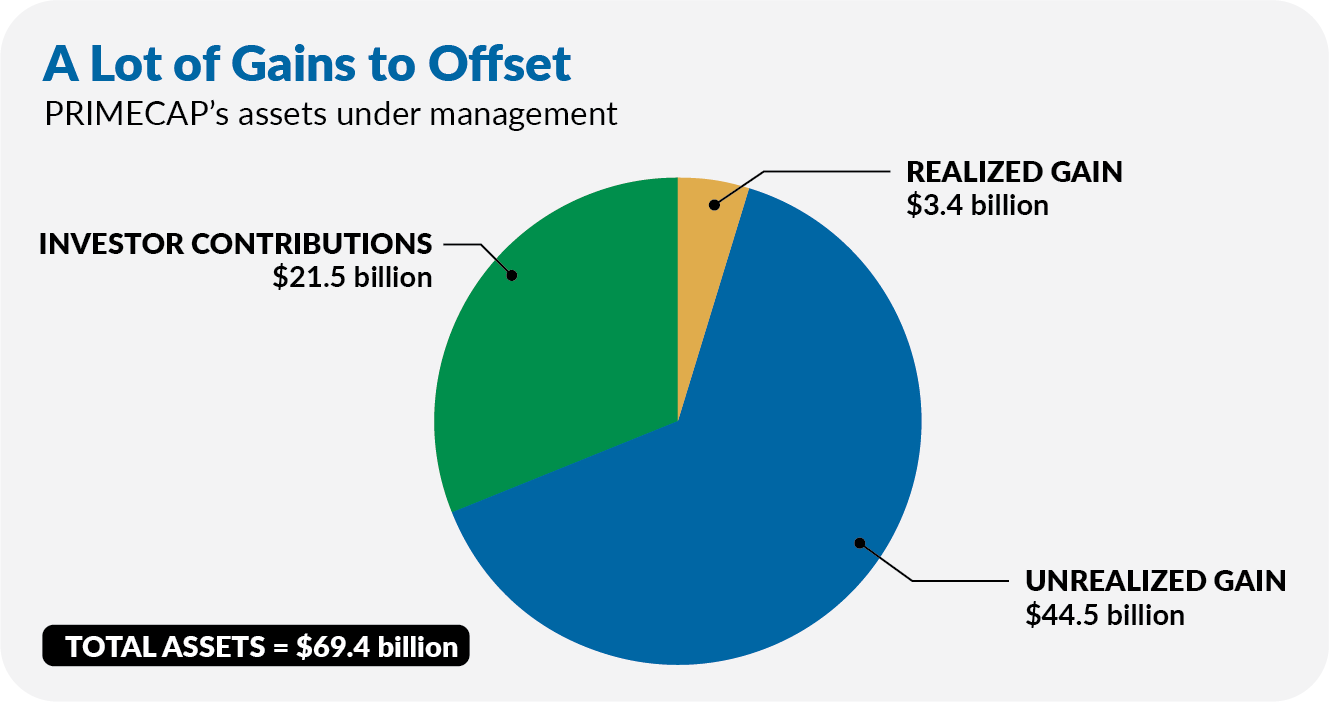

Using PRIMECAP as an example. At the end of April, the fund held $69.3 billion in assets. Vanguard reports that 64% of that total are unrealized gains, and 5% are realized gains. In other words, just 30% of the fund’s assets—roughly $21.5 billion—are direct investor contributions.

The remaining $47.8 billion in assets stems from the managers’ investment success. Of those gains, the vast majority—$44.5 billion—are unrealized, while $3.4 billion have been realized profits this year.

Now, consider that Vanguard’s ETFs typically begin with between $25 million and $50 million in assets. Or that none of Vanguard’s factor ETFs, which were seeded with $8 million each in 2018, have more than $1 billion in assets today.

Capital gains have grown in PRIMECAP (and other legacy mutual funds) over time. Slapping a small share class on a mega-sized fund won’t easily make up for all those gains. And yet, we’re expecting an ETF share class of PRIMECAP to wipe away billions of realized gains every year?

PRIMECAP may be an extreme example (given its size and the embedded gains). Still, it illustrates an important point: having an ETF share class doesn’t guarantee immunity from large capital gain distributions.

For example, trading in response to changes in its target index led International Dividend Appreciation ETF (VIGI) to pay a whopping 6% capital gain distribution in 2021.

Without getting into the nitty gritty of ETF tax mechanics (you can do that here), the bottom line is that for the ETF share class to help dilute and offset the gains embedded in the legacy mutual fund, investors will actually have to use the ETF shares.

But that’s no guarantee. Investors may simply continue selling their mutual fund shares in favor of index-based funds, leaving the new actively managed ETF share classes underused or even orphaned. And if those ETF shares don’t attract meaningful assets, they won’t ease the capital gains burden—they’ll just share in it.

As my analysis the other week showed, the PRIMECAP-run funds have lost around 1.0% per year to taxes. If the dual mutual fund-ETF share class structure can eliminate or reduce this annual tax cost, that’s a big win for shareholders, particularly those who own actively managed funds in taxable accounts.

However, we’ve only seen the dual share class structure in action with Vanguard index mutual funds, where capital gain distributions were already few and far between. Plus, money has flowed to index-based funds for the past two decades.

In short, I hope my skepticism is misplaced, but I’ll believe it when I see it in action.

Trading Costs and Complications

Two other things to keep in mind about the ETF structure:

First, you can't close an ETF to limit its size.1 This could prove problematic for funds investing in smaller shares or other less-liquid markets. And it’s not just an issue for small stock funds; any fund with a history of limiting flows, like the PRIMECAP-run funds, will need to think twice before adding an ETF share class.

Second, and I’m repeating myself here, but ETFs are more complicated to trade than mutual funds.

With mutual funds, you can enter your buy and sell orders any time during the day, knowing that you’ll trade at the fund’s closing price (at net asset value, or NAV) at the end of the day. If you’re switching between Vanguard mutual funds in a Vanguard account, you can even exchange directly between mutual funds, staying fully invested in the market.

With ETFs, you must watch the premium or discount (the difference between the fund’s price and net asset value) and the bid-ask spread. Using limit orders is a best practice. You also can’t do direct exchanges between two ETFs or between an ETF and a mutual fund.

In short, ETFs' intra-day liquidity comes at the cost of increased trading complexity.

Structure Matters Less Than Strategy

Which brings us full circle. As long-time readers know, I’m pretty agnostic when it comes to choosing between mutual funds and ETFs.

The dual mutual fund–ETF share class structure promises to lower costs and make actively managed funds more tax-friendly. Putting actively managed strategies on equal tax footing as index funds would be a big win for stock pickers, but let’s see it in practice before calling victory.

The "real" bottom line is that picking between a mutual fund and an ETF will not determine whether you achieve your investment goals.

The question is not how much you invest in funds versus ETFs—it’s how much you save. How much of your portfolio is in stocks versus bonds versus cash? Are you spending time in the market, or are you trading in and out? These are the issues that matter.

The ETF versus mutual fund debate only comes into play once you've answered these much bigger and more critical questions.

Correction 6/3/2025: The first paragraph was updated to clarify that the SEC has not approved dual mutual fund–ETF share classes of actively managed funds.

1 Technically, you could close an ETF—or, to be more precise, the fund sponsor could stop creating new shares of the ETFs. However, this would turn the ETF into a closed-end fund, which could then trade at large discounts (or premiums) to its net asset value. That isn’t what ETF investors are signing up for.

Vanguard and The Vanguard Group are service marks of The Vanguard Group, Inc. Tiny Jumbos, LLC is not affiliated in any way with The Vanguard Group and receives no compensation from The Vanguard Group, Inc.

While the information provided is sourced from sources believed to be reliable, its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Additionally, the publication is not responsible for the future investment performance of any securities or strategies discussed. This newsletter is intended for general informational purposes only and does not constitute personalized investment advice for any subscriber or specific portfolio. Subscribers are encouraged to review the full disclaimer here.